For the past two years, the curriculum revision process has dominated discussions of the faculty senate. Questions about English and humanities requirements, what type of theology and philosophy courses students should take, and whether additional requirements should be added or not have been fiercely debated back and forth.

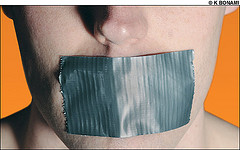

The faculty is divided among their departments, and the monastery is wary of any major change to the core curriculum. There have been meetings, both public and private, and it seems a consensus may in fact be reached in the near future. Despite the many challenges, roadblocks, and false starts on the path to curriculum reform, there is still one group that has not been approached for an opinion – the students.

Students at Saint Anselm are the best group to ask about the quality of the curriculum. We live it every day. We have to register for these courses, incorporate them into our schedules, and complete them each semester. Wouldn’t it make sense to, at the very least, ask for our opinions on whether the curriculum is too heavy?

There have been a few open faculty meetings in Cushing, but they have not been well advertised to students. Often times, the meetings were not advertised at all. Even if they are not going to be consulted, students should be given the chance to hear what changes are going to be made. They have the best insight as to what they like and dislike about the curriculum.

How, then, could the college administration incorporate the opinions and views of students into the reform debate? One way would be through email or an online survey. Faculty and administration never made an effort to contact students about the curriculum changes until after decisions were already made. The argument is not that students know better than everyone else, because they don’t. But they do have important insights that cannot be gleaned elsewhere, and ignoring those insights is beneficial to no one, least of all the students themselves.

Arguably, since no current students will be under the new curriculum, faculty and administration could have assumed that no one cared about the changes. On a campus like ours, which oftentimes seems to suffer from the apathy of at least a decent portion of its student body, this idea does hold some weight.

Some students do care, however, and would like their voices heard. Sending out an optional email giving students the opportunity to respond would have been a way to reach out to those interested.

Why would the school not think of doing something like this? The simple answer is: it’s too complicated.

Once student opinion enters into the equation, it creates another facet to consider in what has long been an arduous and painful decision-making process. Engaged students, it seems fair to hypothesize, would have all different opinions on the curriculum, and sorting those out would take time and consideration.

There is no perfect solution, but that does not excuse the exclusion of the student body from every aspect of the decision-making process. What’s done is done, however, and the curriculum will be changed according to the finalized revisions. Student voices were not heard, and will not be considered on the issue.

It is nice to see that the next major decision the college has to make, concerning the appointment of the new president, will have some student opinion. Margaret O’Leary, History ’14, is a member of the presidential search committee and will represent student opinions in the process. It is a small incorporation of a single student, but this might be one step in the right direction for administration and faculty.