Athletic metaphors are irresistible. They are used by authors divinely inspired (the Pauline Epistle to the Corinthians) and by secular speakers— business professors are warned against alienating students with their overuse. I, too, cannot resist the use of reference to the physical to make a point, in this case, about the intellectual. My image of choice is not the runners of Paul or the idiomatic full-court press of Joseph Hall but rather the wrecked foot of the ballerina.

Ballerinas are cruel people. They are cruel in that they demonstrate, at the very least on the stage, an indifference to suffering. Their feet, deformed, not by birth, as with Richard III, but by will, are a testament to and symbol of that indifference.

Other athletes are cruel: football players turn their brains into jellied eels and MMA fighters become grotesques, but it is the ballerinas, with the vast gulf between their beauty and grace on one shore and their self-torture on another, who best demonstrate cruelty as a prerequisite for achievement.

The Saint Anselm College student would do well to imitate them. The difference between he or she who succeeds and he or she who fails is a capacity for self-denial, an embrace of suffering, and cruelty.

Parents know this. Millions have conducted a version of the “Stanford Marshmallow Experiment,” or, informally, the Marshmallow Test. The experiment, conducted on young children, is an exercise in delayed gratification. To simplify, a child is given a single marshmallow and told that if they do not eat the marshmallow for fifteen minutes, they will be awarded a second. Those who can wait it out and delay their own gratification are more successful in life than those who cannot. They get better SAT scores, earn more, and are healthier. These children, those who can, at a young age, willingly suffer privation, are cruel.

Evolutionary psychologists point to literal sacrifice as a similar effort in delayed gratification. Those who could give up something today in the hope of rewards tomorrow are more successful in life; thus, ritual sacrifice was ingrained within their communities. Even today, in America, the religious are wealthier than the irreligious (Hindus earn the most).

The useful cruelty of ballerinas, children, and paleolithic moon-worshippers is self-directed. Indifference to the suffering of others is both wrong and useless. Rather, the ability to delay gratification, embrace difficulty, and endure discomfort is, as in the ballerina, a necessary capacity for the college student who must exercise cruelty in a way not demanded of them before the half-freedoms of higher education.

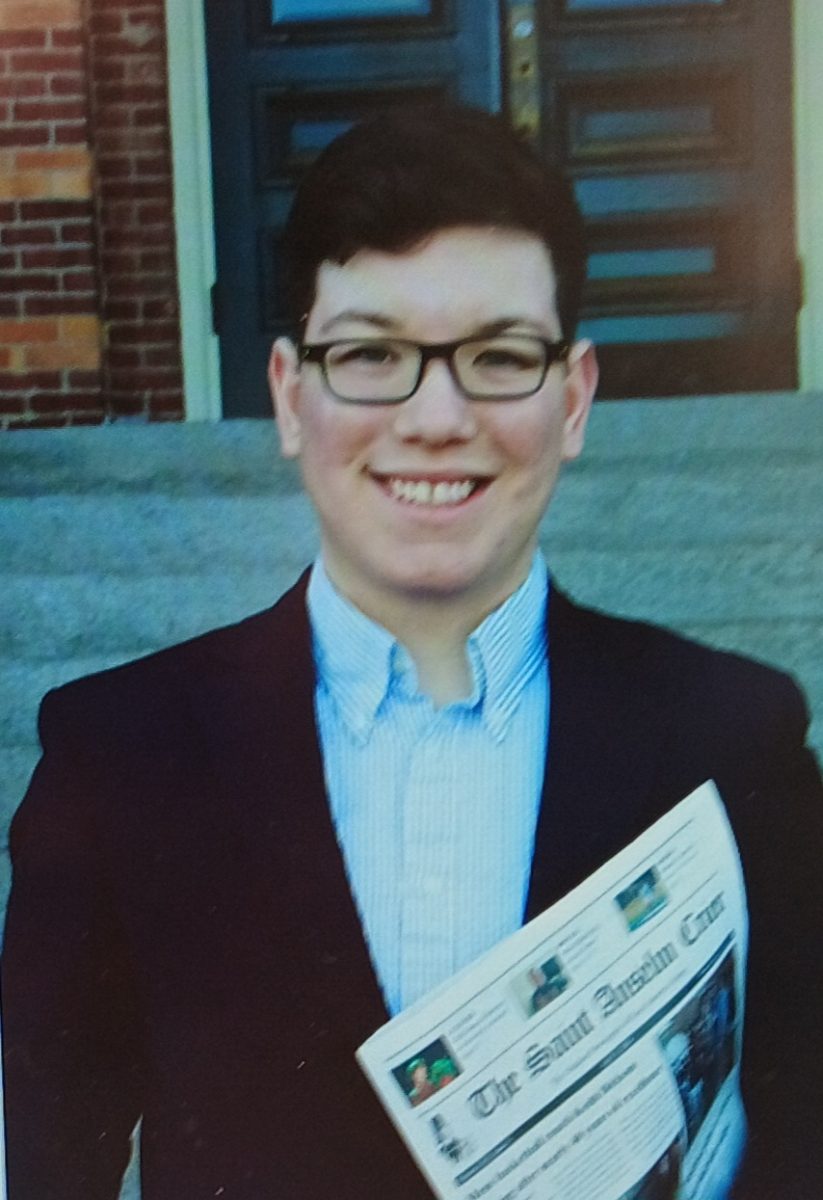

Let us use Johnny as an example. Johnny was not a ballerina (or ballerino) and thus has well-formed feet. His mother woke him up for school each day, and should he have forgotten his homework, a kind teacher would remind him. Johnny’s school maintained a no-zero policy, so he learned that studying was something reserved for the SATs. The incentive structure within which Johnny was raised pushes pleasure-seeking and pain avoidance as ultimate goods: in academics, in friendships, in labor, and in familial relationships.

But, when Johnny arrives at Saint Anselm College, the incentive structures change. First, and perhaps most insidiously, mother is no longer there to tell Johnny to go to class.

He can sleep in if he wants. He can get high and play Warzone if he wants. Should Johnny fail to do his work, he will face no immediate consequences. He can elude uncomfortable social situations should he so desire. Even calling home is optional. Johnny can enjoy many pleasures and avoid many pains here on the Hilltop.

However, should Johnny succeed in his Epicureanism, he will leave here a deficient human being. He will be weak and selfish. He will also be compassionate, at least to himself.

The opposite person, the cruel Anselmian, would succeed where Johnny failed. Certainly, the crueler mirror would earn plaudits, but more importantly, he or she would be, like the athlete, better conditioned for the future.

Just as the ballerina ends practice with performance, we Anselmians end our time here atop a stage. Beneath our robes, the audience cannot tell if we are cruel, and the trinkets that adorn the honored and cum laude mean little, but those who cross that stage with feet and intellects warped, broken, and conditioned by their own cruelty shall wear greater laurels still.