Every evening, the reader in the refectory at Saint Anselm Abbey, mentions what anniversaries of death will be observed the following day. Saint Benedict tells his monastic disciples in the Holy Rule that we are “to keep death daily before our eyes,” and remembering the anniversaries of confreres going home to the Lord is one salutary way of doing it. Still, I was a taken aback a little when the reader noted that “tomorrow [Feb. 5] is the anniversary of the death of Abbot Gerald F. McCarthy, O.S.B., monk and priest of this abbey. He died in the year 2000.”

“Gerald gone a quarter century?” I asked myself. “That can’t be!” And yet was 2025 rolling into its second month. I was in Ireland taking graduate courses at Trinity College Dublin when Abbot Gerald died just a month shy of 88, and so I missed the beautiful funeral rites that surrounded his departure. In many ways, they were identical to the liturgical ceremonies each and every monk at Saint Anselm has, but with perhaps a little more flourish in honor of the responsibilities he once carried as the leader of our Benedictine community.

Heading back to Ireland in January of 2000 occasioned some tears. His health had been declining for some months, so Abbot Gerald’s death was no surprise – but his loss still hit hard. It was, in many respects, not simply the death of an aged confrere, but the end of an era. For many at Saint Anselm College, as well as for alumni of the past two, even three decades, Abbot Gerald is probably just a name on a plaque or a memorial card, but for those who knew his times, what an era it was – and what an amazing life he lived and legacy he left!

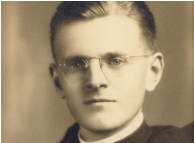

Born March 7, 1912, in Holyoke, MA, to Irish immigrant parents, Gerry McCarthy came to Saint Anselm on a basketball scholarship. He entered the abbey after college studies, pronounced first vows July 2, 1934, and was ordained a priest June 3, 1939. In due course, Abbot Bertrand Dolan, O.S.B., first abbot of Saint Anselm, sent Father Gerald to pursue a graduate degree in sociology at The Catholic University of America, Washington, where he also served as superior for the abbey’s house of studies. Among his teachers was the late Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen. Father Gerald served in the U.S. Air Force as a chaplain during the Korean War. Upon his return to Saint Anselm, he taught and became president of the college from 1956 to 1960. He was prior of the monastery, and due to Abbot Bertrand’s declining health, Father Gerald was elected coadjutor abbot July 8, 1963. Upon Abbot Bertrand’s death in 1968, he became the second abbot of Saint Anselm, with his blessing Sept. 3 of that year. He retired Dec. 23, 1971.

When the great British architect Sir Christopher Wren was completing the touches on his magnificent baroque Saint Paul’s Cathedral, London, he had inscribed on the floor under the great dome – which became one of the great symbols of British resolve during World War II – “Si monumentum requiris circumspice,” or ”If you would seek my monument, look around you.” With slight adaptation, that same sentiment might be expressed for Abbot Gerald. So much of the college campus was conceived, designed, constructed and funded through his ability to draw collaborators into his orbit. Abbot Gerald, I think, would readily admit he was not a renowned scholar or writer, not a great innovator or organizer – but he knew how to get things done, he understood how to touch the heart and he knew how to plant the seeds of inspiration. Plus, in his youth, he could shoot hoop well enough to attract the interest of the Hawks!

One outstanding exercise in making connections was the pivotal role Abbot Gerald played in saving Benedictine life in Korea during and after the war. Between 1949 and 1952, the communists drove the monks from their famous Tokwon Abbey, some were beaten, others executed and many imprisoned. Benedictine sisters from a neighboring monastery suffered a similar fate. The cause for their canonization as saints is under way in Rome. Abbot Gerald and his chaplain’s assistant, who doubled as his driver, tallied miles and miles on his Jeep in efforts to keep them together and find them new homes. And so he did. The result is today’s Waegwan Abbey in South Korea, with more than 130 monks! The Benedictine nuns built Daegu Priory in South Korea, now more than twice the size of Waegwan.

Abbot Gerald remained in touch with both communities over the years, and, providentially, two sisters from Daegu arrived in Manchester only days before his death. They were in the U.S. on other business, but made time to come to New Hampshire to meet and thank the famous monk chaplain who had helped save their community. They managed to visit him in his room at Catholic Medical Center just in time. At Abbot Gerald’s funeral Mass, attended by bishops from throughout New England, and many church and civic dignitaries, the two Korean sisters sat in a place of honor.

With the unfailing assistance, wise guidance and administrative genius of his confrere and dear friend, Fr. Bernard G. Holmes, O.S.B., who served as a mathematics professor, treasurer and president of Saint Anselm at various times, Abbot Gerald spearheaded a major expansion of Saint Anselm in the early 1960s. Proportionately, it was said to be the largest expansion of a Catholic college or university in the U.S. until that time. In short order, the Hilltop found itself with a cadre of committed donors, busy architects and careful engineers intent on opening a library, science center, gymnasium, several dorms and a wing to the monastery, as well as a stunning abbey church. The names Geisel, Perini (now Goulet), Stoutenburgh, Bertrand, Brady and Dominic became part of the lexicon of Saint Anselm, with Carr, Jeanne d’Arc and Davison soon to follow. Saint Raphael Parish, established in 1888, just a year before the college’s foundation, likewise saw a new church, graceful and beautiful, and a new grammar school rise on Manchester’s West Side, where Benedictine life in New England began.

Abbot Gerald’s determined ability to share – gently but convincingly – a vision of what the college and parish could become, coupled with Father Bernard’s organizational skills, attracted “buy in” from business leaders and professionals with the financial and social capital to widen the circle of financial support. The college’s first advisory board of trustees was a critical first step in a process of involving lay men and women as essential collaborators with the Benedictine community here. One of Abbot Gerald’s hallmark gestures was to remind his conversation partner that any success depended upon a relationship of trust, respect and shared commitment among “you, me and God.” As he mentioned the triad, his right hand would gesture outward toward his partner, backward toward himself and upward toward the Lord. As the years rolled on, he was still making the point, but sometimes his words, timing and gestures would not line up quite as directly as he intended such that he became you, you became God and God became him! I would have look at my papers or books whenever that would happen because it would make me smile, but I always took it as a subtle reminder that we are all members of the Mystical Body of Christ, interpenetrated by God’s love! And we all must cope with the years!

Seeing Abbot Gerald strolling about the campus, or simply in the cloiser, with Father Bernard always elicited a smile. They could look ethereal on a spring or fall day with their habits catching the breeze, and in the cold weather, with their fedoras and topcoats, they were dapper ambassadors from an earlier era. During his last years, every visit to clean his rooms, take in a supper tray or bring him the Eucharist was always rewarded with a little chat – sometimes even a conspiratorial one. Once he wanted assistance to arrange a special luncheon in the guest refectory for a lady and her daughter. Menu, flowers, linens, wine and tea all had to be just right.

“Now, Jerome, don’t forget the tea!”

“Surely not. You’ll have Irish Breakfast tea, Father, steeped and piping hot.”

When the lady and her companion arrived, they were received by Abbot Gerald with the utmost graciousness and charm – and, perhaps, just a flutter of his heart. There was a story somewhere in all this, but it was not mine to hear. Still, it was a privilege to help him arrange it.

Abbot Gerald’s time as leader of our community was certainly eventful, but it was not easy for him, I can imagine. The liturgical and attitudinal changes occasioned by Vatican II (1962-1965) hit full force – and, happily, their implementation here was gradual and largely successful. The Vietnam War was blazing, and as U.S. casualties mounted, and government honesty proved questionable, opposition to American involvement swept onto this campus too. In the wake of U.S. incursion into Cambodia, a student walkout emptied classrooms and filled the upper common, the only quadrangle at the time. One of his monks was arrested and charged for an incident at a Milwaukee draft office. For an Army chaplain during the Korean War, flag burnings, protest marches and anti-U.S. placards were shocking and more than a little infuriating. Perhaps the biggest challenge Abbot Gerald and his monks faced in 1960s was the steady erosion of vocations here and throughout the U.S., Canada and Europe. Monks, some solemnly professed, others in simple vows, left the abbey to marry, to serve in activities different from higher education and parish ministry, to explore other lifestyles and some even left the Church altogether. Adding to the problem, the number of young men seeking entry into the monastic life at Saint Anselm dried up, though never entirely.

Toward the end of his life, I asked Abbot Gerald, presuming the necessary support from the abbot and community, how he would feel about a “welcome, home” event for those who had left the cloister and their families, something many monasteries and other religious communities had been doing to promote reconciliation, renewal and harmony. To my surprise and delight, he brightened, and in quiet tones, said, “Oh, how I would love to see them again! Yes, I would support that.”

His interest in young people and the promotion of religious life for men and women never left Abbot Gerald. When I was a first semester freshman back in the fall of 1971, just before Abbot Gerald’s resignation at the end of that year, I asked him to bless my newly acquired college ring. I thought it was the coolest ring I’d ever seen, and blessing the ring was the custom at home. I saw him after Vespers one night, and he beckoned me to sit down on a pew in the choir area. He blessed the ring but then drew me into conversation about a much bigger and more important topic – my plans and hopes in life. There began a series of discussions we would have, off and on, throughout my time as an undergraduate. To this day, I cherish them.

Over the years until just before his death in on February 5, 2000, Abbot Gerald kept having similar chats with young men and, sometimes, young women. Occasionally, I stop and greet them, and whisper into his ear, “Come into my web, said the spider to the fly!” He would chuckle, then smile broadly, yet his was never a web of entrapment. It’s God’s web of invitation and commitment, life and love. We all need to be caught up in it somehow for it is how we find purpose in life, our individual vocation, .

By the time I was ready to take my degree, and go off to challenge the big world, I knew what God was asking of me and where. Even though it took me almost 15 years to provide an answer, the question, the invitation and the inspiration came – and it came because of God’s grace, persistence and the web of “me, you and Him” that Abbot Gerald started spinning in hushed tones one windy, rainy night in the abbey church. Thank you, Father Abbot! I try to spin that web myself – and often shake my head and smile. Keep us all in your prayers!◄

“Blessed be the Lord, who has shown me the wonders of his love in a fortified city!” Psalm 31.

Therese Dame • Feb 21, 2025 at 9:45 pm

What a wonderful tribute to Abbott Gerald!

Brian Flaherty • Feb 21, 2025 at 7:33 pm

I was fortunate to get to know Abbot Gérald during my years at Saint Anselm. I interviewed him for a paper I was writing for my Journalism class and spent a lot of time with him after that. I have a picture of the two of us from the day I graduated in 1998. Like Fr Jerome, Abbot Gérald encouraged me to consider a vocation. After he died I had a dream that I became a priest and my first Mass was on the feast of St Agatha. When I woke up I looked up when the feast of St Agatha is…it’s Feb. 5, the day Abbot Gérald died.

Prof. Thomas Lee • Mar 24, 2025 at 3:32 pm

I arrived on campus as a new faculty member when Abbot Gerald began his service as Abbott. He was always kind and generous to me in many ways, and his friendship is a warm memory.