The myth of Seneca Falls: A retelling of the women’s suffrage movement

Tetrault was inspired after a visit to Rochester, NY, the home of Susan B. Anthony (DAVID MICALI/CRIER)

April 1, 2019

Students were surprised to learn that the stories that are told about the women’s suffrage movement are the result of a PR campaign created by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

This is according to Associate Professor Lisa Tetrault of Carnegie Mellon University and author of the book “The Myth of Seneca Falls.” Professor Tetrault spoke to a crowd about her book at the Jean Student Center on March 20.

Professor Tetrault’s book came out of a visit to the home of Susan B. Anthony in Rochester, NY. There, a tour guide erroneously told her that Susan B. Anthony wanted to attend the Seneca Falls Convention, but was teaching at the time, so she sent her family in her place. Though it is likely that Susan B. Anthony did not know of the Convention at the time, people like to tell the myth that she did, and in some cases, tell that she was there. Professor Tetrault became fascinated with these myths people tell and discovered that the myths are as interesting as the facts.

The story, as it stands, is that in 1848, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton decided to hold the First Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, NY. There, they drafted a document with 12 points with the ninth point being that women should have the right to vote. This point was contentious, and it was only after freed slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass put his weight behind it did it pass. Stanton would meet Susan B. Anthony in 1851 and the two women would spend the rest of their lives fighting for women’s right to vote. This story, Professor Tetrault contends, is a political weapon of the post-Civil War era and was used by Anthony and Stanton to fight their political battles and obstacles.

Professor Tetrault then told the true story of the fight for Women’s Suffrage. The Women’s Rights Movement began in the 1820s and 1830s with the anti-slavery movement. Female abolitionists would often find themselves being attacked for being out in the public and discussing things such as politics and slavery. These women began defending themselves and a woman’s right to be a part of the public discord.

Following the Civil War, Congress was debating a series of amendments to the Constitution to give freed African American males the right to vote. One of these amendments was the 15th Amendment which declared that the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied… on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Frederick Douglass was fighting to get it passed and he called upon Elizabeth Cady Stanton to support it, much like how he supported the woman’s right to vote at the Seneca Falls Convention. Stanton responded that it would be a grave injustice to give black men the right to vote before giving it to white women and, according to Professor Tetrault, Douglass’s response was “how could you [do this]?”

Following the incident, Stanton and Anthony would break away from the main women’s rights movement and start their own faction called the National Woman Suffrage Association. Stanton and Anthony joined forces with Victoria Woodhull, a spiritist who believed she could contact the dead and the first woman to run for president in 1872. Woodhull owned a newspaper, the Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, and published an article outing the leader of the main women’s rights movement for cheating on his wife. This plan backfired and brought the attention of the national press down on the woman’s suffrage movement, which they dubbed as advocating “free love.” The press also dubbed Woodhull as Ms. Satan, leading women astray. Several people within the women’s rights movement saw Stanton and Anthony as doing more harm for the cause than good.

By 1873, Stanton and Anthony needed a distraction, so they declare that year’s Seneca Falls Convention to be the 25th Anniversary Convention. It was there that they learned that by shaping and retelling the past, they could successfully fight political battles in the present. Conveniently, none of Stanton’s rivals, such as Lucy Stone, were at Seneca Falls, so Stanton could claim that she was the movement. Additionally, Stanton and Anthony put suffrage at the center of the movement. Suffrage, at the time, was only part of the movement. Others, such as Stanton and Anthony’s rivals were focused on workers’ rights, safety, equal pay, temperance, and women’s reproductive rights. With Stanton and Anthony’s retelling, suffrage was always the true cause and goal of the movement. Stanton and Anthony wrote a three-volume history of the women’s suffrage movement in 1876. In their telling of history, they are at the center and, as for their rivals, they write “there was a secession in our ranks.” Professor Tetrault explained how in the post-Civil War era, “you don’t use the word ‘secession’ lightly.” One could even argue that Stanton and Anthony were the ones that seceded from the women’s rights movement.

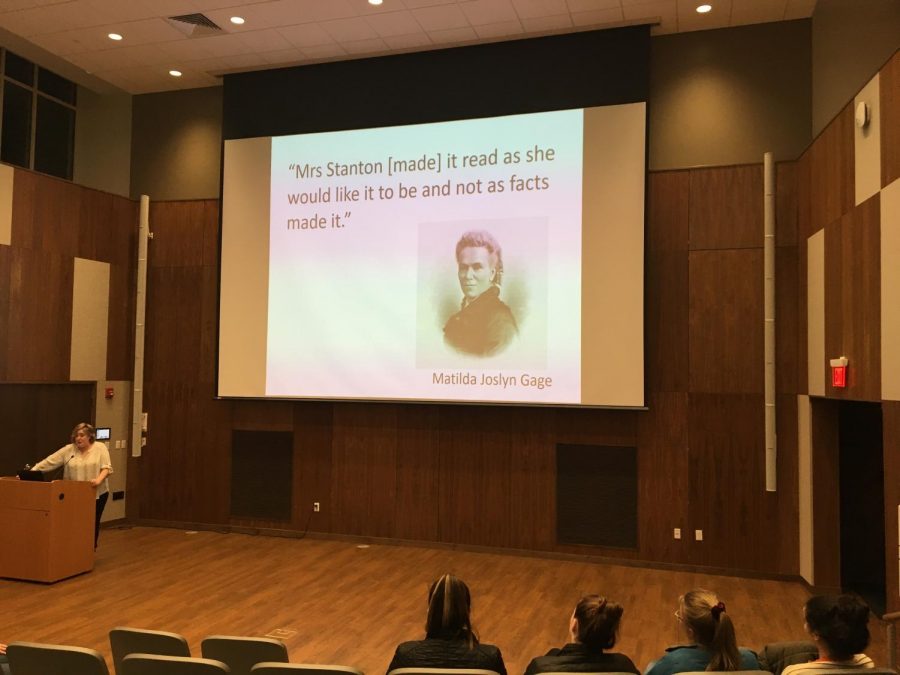

Women’s Rights activist Matilda Joslyn Gage said of the book at the time, “Mrs. Stanton [made] it read as she would like it to be and not as the facts made it.”

In 1888, at the 40th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention, Stanton and Anthony declared that Seneca Falls was the beginning of women’s rights in the whole world. Lucy Stone, the leader of the rival faction, wrote at the time that she should “puncture the bubble that the Seneca Falls meeting… was the first public demand for suffrage,” though she ultimately decided that she could tell her history when she no longer had work to do in the present. Her name and her involvement in the Women’s Rights Movement would be forgotten by history.

In 1896, Stanton wrote an editorial saying the Bible and Christianity was the root of women’s suffering. Stanton was subsequently kicked out of the movement and replaced by Anthony.

At Susan B. Anthony’s home, Anthony had one of the largest archives of the history of the women’s rights movement in the world. Anthony had a three-volume biography written of her and, after writing the book, burned all the documents in the archive. According to Professor Tetrault, Anthony knew exactly what she was doing when she did this. An advertisement for her book stated, “this is the only authentic biography of her that can be written, as the letters and documents will not be accessible to other historians.”

Professor Tetrault explained how Susan B. Anthony was a real person and a “complex, savvy politician.” Professor Tetrault hoped that her book, “The Myth of Seneca Falls,” would undo, or start to undo, this Seneca Narrative created by Stanton and Anthony. Although this narrative helped win women the right to vote, it sidelined other issues that still affect women to this day, such as equal pay or reproductive rights. Whether or not this narrative benefits society was up to the audience’s interpretation.